BBC

BBCFor years, Russia and Syria have been key partners – Moscow has gained access to air and naval bases in the Mediterranean, while Damascus has received military support for its fight against rebel forces.

Now, after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, many Syrians want Russian forces gone, but their interim government says it is open to further cooperation.

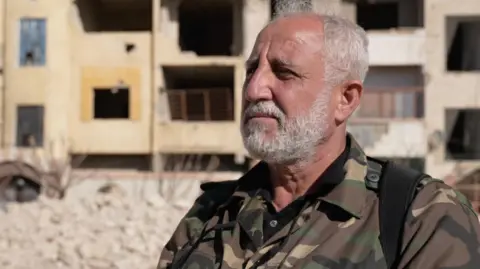

“The Russian atrocities here were beyond description,” said Ahmed Taha, a rebel commander in Douma, six miles northeast of the capital, Damascus.

The city was once a prosperous place in the region known as the “breadbasket” of Damascus. And Ahmed Taha was once a civilian, working as a trader when he took up arms against the Assad regime after a brutal crackdown on protests in 2011.

Whole residential neighborhoods in Douma now lie in ruins after some of the fiercest fighting in Syria’s nearly 14-year civil war.

Moscow entered this conflict in 2015 to support the regime when it was losing ground. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov later claimed that at the time of the intervention, Damascus was only weeks away from the rebels.

The Syrian operation showed Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ambition to be taken more seriously after widespread international condemnation of his annexation of Crimea.

Moscow claimed to have tested 320 different weapons in Syria.

He also secured a 49-year lease on two military bases on the Mediterranean coast – the Tartus Naval Base and the Hmeimim Air Base. This allowed the Kremlin to rapidly expand its influence in Africa, serving as a springboard for Russian operations in Libya, the Central African Republic, Mali and Burkina Faso.

Despite the support of Russia and Iran, Assad could not prevent the collapse of his regime. But Moscow offered refuge to him and his family.

Now many Syrian civilians and rebel fighters see Russia as complicit with the Assad regime that helped destroy their homeland.

“The Russians came to this country and helped the tyrants, the oppressors and the conquerors,” says Abu Hisham as he celebrated the fall of the regime in Damascus.

The Kremlin has always denied this, saying only jihadist groups such as IS or al-Qaeda were targeted.

But the United Nations and human rights groups have accused the regime and Russia of committing war crimes.

In 2016, during an assault on densely populated eastern Aleppo, Syrian and Russian forces carried out relentless airstrikes, “claiming hundreds of lives and reducing hospitals, schools and markets to rubble,” according to a UN report.

In Aleppo, Douma and elsewhere, regime forces surrounded rebel-held areas, cutting off food and medicine supplies, and continued to bombard them until armed opposition groups surrendered.

Russia has also negotiated ceasefires and agreements to surrender rebel-held towns and cities, such as Douma in 2018.

Ahmed Taha was among the rebels there who agreed to surrender in exchange for safe exit from the city after a five-year siege by the Syrian army.

He returned to Douma in December as part of a rebel offensive led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa.

We returned home in spite of Russia, in spite of the regime and all those who supported it, says Taha.

He has no doubt that the Russians should leave: “For us, Russia is an enemy.”

This is an opinion echoed by many people we talk to.

Even the leaders of the Syrian Christian communities, whom Russia has promised to protect, say that Moscow has helped them little.

In Bab Touma, the old Christian quarter of Damascus, the patriarch of the Syrian Orthodox Church says: “We have not had the experience of Russia or anyone else from the outside world protecting us.”

“The Russians were here for their own benefit and goals,” Ignatius Aphrem II told the BBC.

Other Syrian Christians were less diplomatic.

“When they came in the beginning, they said, ‘We came here to help you,'” says a man named Assad. But instead of helping us, they destroyed Syria even more.

AFP

AFPSharaa, now the de facto leader of Syria, said ua interview for the BBC last month that would he did not rule out allowing the Russians to stay, and he described the relations between the two countries as “strategic”.

Moscow seized on his words, with Foreign Minister Lavrov agreeing that Russia “has a lot in common with our Syrian friends.”

But untangling the ties in a post-Assad future may not be easy.

Rebuilding the Syrian military will require either a fresh start or continued reliance on Russian supplies, which would mean at least some kind of relationship between the two countries, says Turki al-Hassan, a defense analyst and retired Syrian army general.

Syria’s military cooperation with Moscow predates the Assad regime, says Hassan. Almost all the equipment he has was produced by the Soviet Union or Russia, he explains.

“Since its inception, the Syrian army has been armed with Eastern Bloc weapons.”

Between 1956 and 1991, Syria received from Moscow some 5,000 tanks, 1,200 fighter jets, 70 ships and many other systems and weapons worth over $26bn (£21bn), according to Russian estimates.

Much has been made of Syria’s wars with Israel, which have largely defined the nation’s foreign policy since it gained independence from France in 1946.

More than half of that amount remained unpaid when the Soviet Union collapsed, but in 2005 President Putin wrote off 73% of the debt.

For now, Russian officials have taken a conciliatory but cautious approach toward the interim rulers who ousted Russia’s longtime ally.

Vassily Nebenzia, Moscow’s UN envoy, said the recent events marked a new phase in the history of what he called the “brotherly Syrian people”. He said Russia would provide both humanitarian aid and reconstruction support to enable Syrian refugees to return home.